Essay 5

The (Mis)Alignment of Global and National Priorities for Education

By Lee Crawfurd and Susannah Hares

Introduction

“Education, Education, Education!” declared Prime Minister Tony Blair, as he laid out priorities for his government after his resounding election victory in 1997. In the decade that followed, Blair’s government recruited 35,000 teachers, cut class sizes, increased teacher pay, built 1,000 new schools, introduced compulsory literacy and numeracy time in primary schools to drive up standards, and launched innovations like the academies programme.

Blair had the fortune of presiding over a rich economy, and he lavished cash on the education sector. Core per pupil funding rose by nearly 50 percent in real terms over the decade. The onlypriority was raising standards, whatever it took.

Developing countries don’t have a lot of cash to lavish. In The Pathway to Progress on SDG 4, Girin Beeharry notes that trade-offs are made all the time because there is simply not enough money to go around. And so, amid a plethora of needs, Girin urges donors to prioritise foundational numeracy and literacy—early grade reading and numeracy programmes—with close monitoring of progress and strong accountability for results.

It’s a compelling essay, exploiting Girin’s front-row seat to the deliberations of the education aid architecture over the last few years to make cutting insights and concrete and provocative proposals to address what he sees as the failures of the industry. And it’s a rare call for urgent prioritisation in a sector that prefers to demand more money than discuss where trade-offs need to be made.

Prioritisation: Everywhere and nowhere

As Girin notes, it’s impossible for member-state organisations like UNESCO or constituency-based organisations like the Global Partnership for Education to prioritise. They must serve all their members and constituents. And it’s almost impossible for governments to prioritize just one aspect of education. Their citizens have a range of views on what is important. So, with citizen preferences and donor influence at play, should governments in developing countries prioritise early grade literacy and numeracy?

If governments care only (or mostly) about achieving mass human capital, then there is a case to be made for prioritising early grade literacy and numeracy.

We see two principal objections. First, there are precious few examples of success to point to. Making foundational literacy and numeracy a priority aim does not mean that governments or donors know what to do to achieve this aim.

Second, parents and governments do—and should—have other priorities that are just as legitimate as building mass human capital—socialisation and child wellbeing, for example.

It may be fair to prioritise foundational skills if the goal is achieving mass human capital

The case for prioritising early grade reading and maths over other educational goals is that foundational learning is a critical input into other learning goals. Without ensuring universal basic literacy and numeracy, children may gain little additional learning from expanding access to preschool or secondary school.

The argument makes good sense. The association between foundational skills and subsequent cognitive ability and staying in school for longer (with all the benefits that brings) has a wide array of evidence behind it. There is also good evidence for the association between foundational skills and adult outcomes, and even human capital investments in the next generation. However, as Girin points out, there is not (yet) convincing causal evidence on the link between foundational skills and these life outcomes. It is not possible to isolate the impact of foundational skills from a host of other characteristics (e.g., parental support) that might be associated with those skills.

While foundational skills yield certain inarguable benefits, the case for prioritizing them ahead of all other human capital investments—early childhood education or universal secondary education, for example—remains to be made quantitatively.

Those interested in increasing momentum for the early grade reading and maths agenda would do well to prioritise research that disentangles the link between foundational skills and better life outcomes from other factors.

An important part of this is first showing that it is even possible to improve foundational skills at scale, and then second, showing that such efforts do indeed yield the hoped-for downstream benefits. One way of doing this would be through following up on big foundational literacy randomized controlled trials, such as the Tusome programme in Kenya. By measuring the long-term outcomes of children who received (and did not receive) interventions that have successfully improved foundational skills, we can understand whether foundational skills have a causal relationship with better life outcomes. If this is indeed the case, education donors will have a stronger argument for investments to improve foundational skills.

For literacy and numeracy to be a priority, governments need a better grip on student learning

For governments to prioritise investments in foundational skills, they need to know if they have a problem, and how to fix it. The premise of the ASER and Uwezo surveys conducted for the last decade in South Asia and East Africa is that without widespread understanding of low learning levels, little action will be taken.

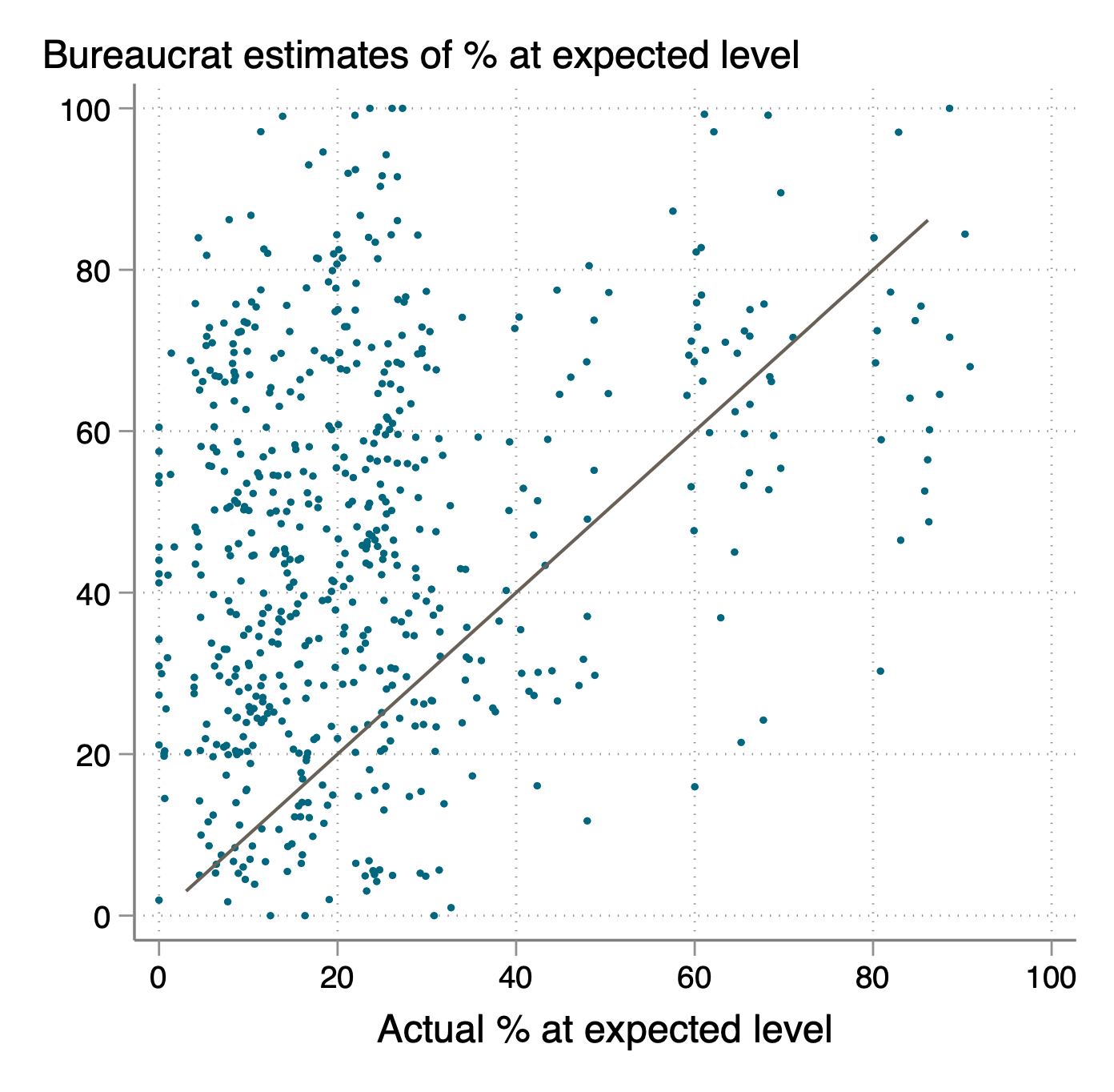

In a paper to be published later this year, Crawfurd et al. (2021) interviewed 924 education officials from 36 low- and middle-income countries, finding that knowledge of the state of literacy and numeracy levels in their country was low. Whilst the majority (80 percent) agreed in the abstract that there is a learning crisis, most drastically under-state the scale of the problem. When asked to estimate the share of students that can read by the age of 10, the majority (79 percent) overestimate.

Figure 1. Estimated versus actual number of children who can read at age 10

Notes: Actual percentage at expected level is the inverse of “learning poverty.” Learning poverty estimates are available for five countries, with the remaining 31 estimated using harmonised learning outcome scores (Crawfurd et al., 2021).

On average, officials estimated that 63 percent of children can read by age 10. This compares to World Bank estimates based on actual national learning assessments for the same 36 countries of just 25 percent. Whilst estimates of learning are poor, officials are much better at accurately estimating the amount of schooling children receive and per pupil spending.

A lack of understanding that there is a problem to address is clearly one barrier to greater investment in foundational skills. Another barrier is a lack of belief in the availability of solutions. A common view is that education systems have often focused more on identifying or selecting the most talented students for higher education than on building universal skills (Muralidharan and Singh 2021). A related idea is Carol Dweck’s concept of “growth mindset.” People with a growth mindset think that intelligence is not fixed but can be improved with effort. Crawfurd et al. (2021) assessed the growth mindset of government officials. The majority (64 percent) believe that intelligence is fixed. If governments don’t truly believe that some children are capable of learning, it seems unlikely that they will.

Governments (and citizens) do (and should) care about more than just human capital

Despite efforts by some donors to concentrate public spending on primary education, the reality is that governments in every country care about more than the accumulation of human capital.

Policymakers spend large shares of education budgets on secondary education, and universal secondary education has been a popular manifesto pledge in African elections for many years (although notably, as discussed above, it’s not clear that investments in foundational skills are any more effective at human capital accumulation than investments in universal secondary education).

It’s well documented that historically a central role of education systems has been the socialisation of citizens. For example, US states adopted universal schooling as a nation-building tool to instil American civic values to the diverse waves of migrants during the “Age of Mass Migration” from 1850 to 1914 (Bandiera et al. 2018).

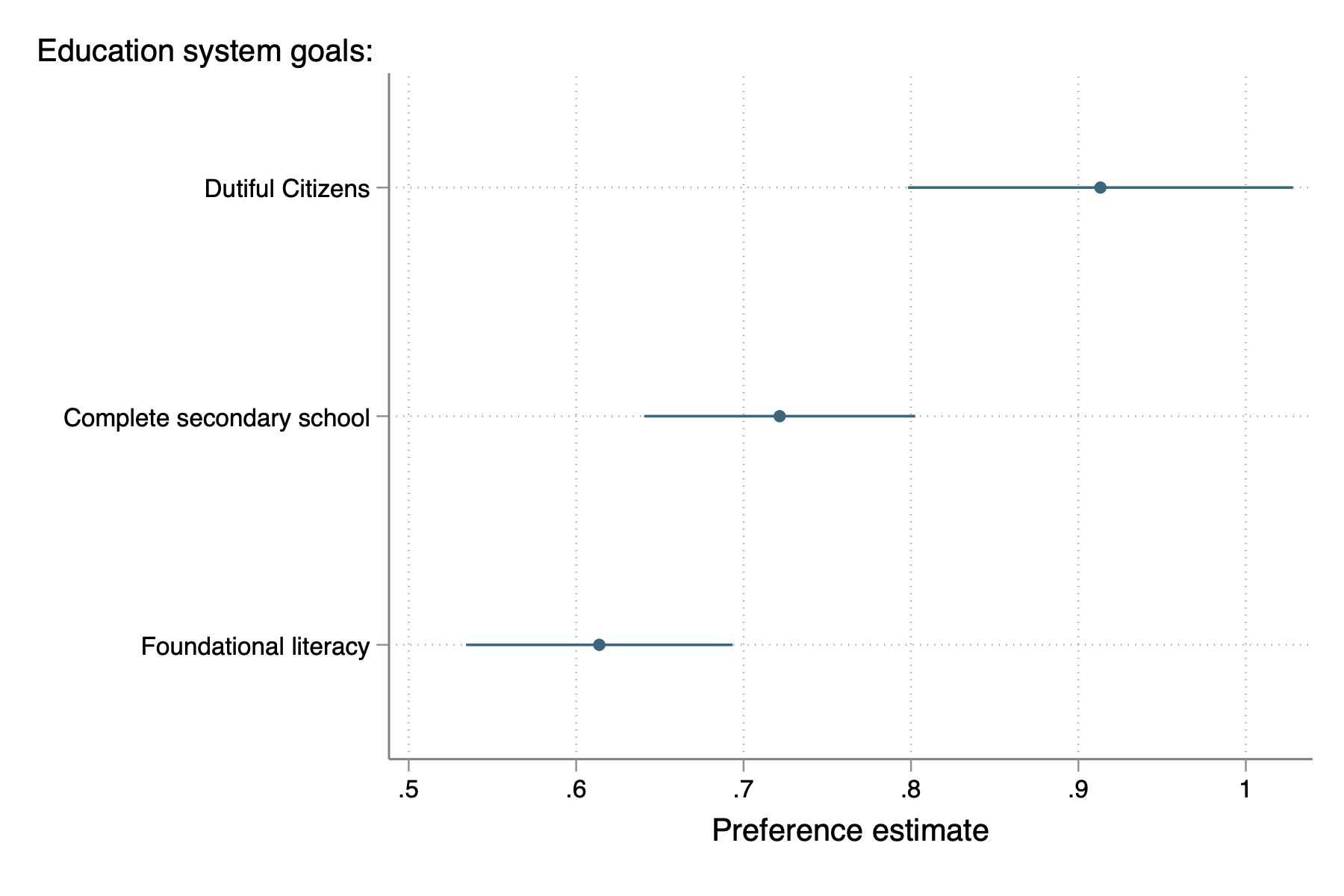

But how much weight do policy makers place on different goals of education systems? Crawfurd et al. (2021) asked officials to make a set of quantitative trade-offs between different objectives— universal basic skills, universal schooling, or socialising children to become “dutiful citizens.” Of these three, the production of “dutiful citizens” is valued more than the other outcomes. Quantitatively, a dutiful citizen is worth 50 percent more to officials than a child learning how to read.

Figure 2. Officials’ goals for education systems

Source: Crawfurd et al., 2021.

Source: Crawfurd et al., 2021.

It’s not just what officials care about that matters. As Girin notes, there is not enough electoral demand for quality primary education. In a democracy, governments respond to citizen preferences. And it’s not clear that citizens prioritise literacy either. Uwezo, an annual household-based survey that measures children’s literacy and numeracy, tested 130,000 kids in their 2014 survey and found that only 30 percent of grade three kids were able to do grade two work, dropping to just 25 percent of kids in rural areas.

Following the release of the survey data, researchers reported the dire results of the tests to a randomly assigned group of 550 Kenyan households. The information had no effect. Parents who received the information were no more likely than other parents to take action at school or in the public sphere to improve the quality of their children’s schooling, or to adopt behaviors at home that might have a positive impact on their children’s learning.

Keeping children safe matters at least as much as learning

Developing countries have preferences for the outcomes of their education system and they have priorities for new investments and interventions. Donors should help support those priorities, rather than impose top-down global priorities on them. But where donors doinfluence priorities, it’s a puzzle to us why donors do not do more to ensure that children are safe in school, to protect the real foundation for education.

Figure 3. Percentage of 15-year-olds reporting sexual harassment at school by a teacher or other staff member in last four weeks

Girls and boys face significant rates of physical and sexual violence in school, often by their teachers. While we lack reliable and up-to-date data about the scale and nature of school violence, various surveys shed light on the crisis. PISA for Development, for example, a set of education assessments focused on developing countries, asks students if they have experienced unwanted or inappropriate language or touching by their teachers. One in eight boys and girls in Senegal and Zambia report having been sexually harassed by a teacher or staff member within the last four weeks.

Donor efforts to run literacy interventions in school will be worth little if girls and boys are assaulted by their teachers in their classrooms.

Conclusion

Girin’s call for a frank discussion about priorities is welcome in a sector where such conversations are rare. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the international community is making urgent calls to protect—and even increase—education spending. But we know difficult trade-offs will need to be made, and Girin’s manifesto should be in the minds of all education leaders as they consider those trade-offs. And his sense of urgency is much needed in a sector that seems to drift further and further away from the 2030 SDG targets, with no plan to get back on track.

Girin makes the case to invest in foundational skills better than anyone. But, urging donors to prioritise early grade reading and math, when developing countries have multiple, legitimate, goals for their education system, is problematic. It’s important to note, however, that Girin is not demanding that priorities shift wholesale—instead, he suggests that a “coalition of the willing”, i.e., those already persuaded of the need to prioritize early grade literacy and numeracy.

We could be more persuaded if the limitations we describe above were addressed first: better causal evidence demonstrating the link between foundational skills and life outcomes, and an urgent and primary focus on making children safe from harm in school.

Individual parents, children, and elected governments may all differ in their goals and ambitions from education. But we don’t think learning to read is an unambiguously higher priority than avoiding child abuse.

Girin’s essay will make a mark on the sector. His intolerance of the learning crisis shines a light on our collective failure to agree and implement practical steps to fulfil the promise of education for those who need it most. Girin’s passion for progress is palpable, and now—nine years before the SDGs expire—is the time for the sector to take heed and take action. Things can only get better.