Essay 9

The Three-Legged Stool Approach to Advancing Basic Learning in East Africa

By Youdi Schippe, Risha Chande and Aidan Eyakuze

Introduction

In his essay “The Pathway to Progress on SDG4”Girin Beeharry calls for leadership in the education aid architecture, focusing attention mainly on multilateral funding agencies and bilateral donors.

He argues for a focus on three main things. First, define clear priorities: if you try to do everything, you end up doing nothing. The policy priority he advocates for is foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN). His priority targets are low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Second, he calls for monitoring progress towards those priorities. It is lamentable that basic questions about learning progress towards SDG 4 cannot be answered, because the data needed to make meaningful FLN comparisons over time and between countries are missing, not least for sub-Saharan Africa.

Third, he calls on the education aid architecture to use monitoring to create accountability for progress (or lack of it), and to press for change.

Girin closes his essay by inviting civil society and nongovernmental organisations “to use their powerful voices to not only advocate for more spending on education, but to hold countries and the global aid architecture accountable for the collective promises made over the years to improve learning outcomes, starting with FLN.” As a civil society organisation (CSO) working on measurement, monitoring, and accountability in FLN in East Africa since 2009 we at Twaweza are grateful for the opportunity to add our voice, forged from experiment and experience, to Girin’s call.

We agree with the basic leadership profile Girin outlines and his call for prioritizing FLN. His three-legged stool of setting priorities, measuring progress, and instituting accountability or consequences for measured progress is not rocket science, but it is backed by research in the economics of management (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007; Bloom and co-authors, 2014). So there is no reason for this not to work in the architecture of education aid as well.

Importantly, recent evidence suggests that the target-measure-accountability sequence also matters when managing school systems and for improving learning outcomes (World Development Report 2018). We will illustrate elements in this sequence with some examples from our education programs in Tanzania and discuss this in relation to points made in the essay, particularly on the role of CSOs vis-à-vis government.

First leg: Setting targets

The first concrete leg advocated by Girin, prioritising FLN in sub-Saharan Africa, in many ways aligns with the work of Twaweza East Africa. We work in Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda, and within our education-related work, we have always focused on basic skills or FLN. As Girin points out, without FLN progress it is hard to imagine widespread student progress at later stages in their school career.

As in many contexts, in East Africa there are a myriad of political disincentives to prioritizing FLN. Early grade learning is not politically salient compared to more sensitive markers such as primary school leaving examinations. Early grade pupil-teacher ratios are high, and student attrition is intense. A majority of early grade teachers are absent from class, and, when asked, say they would prefer to teach in the upper grades.

Combined with high population growth rates, the early grade learning environment seems destined to deteriorate even further. The continued neglect and illiteracy risk of large numbers of early grade students reflects an apparent political priority.

Second leg: Monitoring

Part of the problem is the relative invisibility of the conditions and outcomes in the early grades in East Africa. This brings us to the second leg: monitoring. We are missing a salient learning performance metric at Grade 2 or 3 level (ages 9-10), one that can become a recognised lodestar for the FLN policy agenda across the region. This is not a new idea: Girin tells policymakers: “[If] you don’t have a learning assessment, make sure you introduce one and ask for support from the development partners.” Bruns and Makyal wrote in 2019: “It is time—indeed, past time—to support a regionwide test that serves all countries in sub-Saharan Africa.” Regionwide tests also have the potential to create more political salience through cross-border comparisons.

Twaweza has long supported independent monitoring of FLN outcomes in Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda. Our Uwezo1 (capability) program focuses on measuring progress towards basic skills (FLN) targets, using simple but sound data collection tools, inspired by ASER/Pratham in India. The data also features other relevant variables, including teacher attendance. We communicate the results to parents and various layers in the education system to create awareness and accountability. According to Uwezo (2019), in Tanzania the percentage of children aged 9-13, both in and out of school, mastering full Grade 2 FLN skills was 42 percent in 2011 and 45 percent in 2017.

When the results of the first Uwezo assessments were made public, there was a strong official backlash. Depending on the country, the official stance has varied between recognition of the results and refusal to provide field permits. We are convinced that the emerging national and international consensus around the importance of FLN outcomes—relative to school inputs—has been facilitated by the evidence on the scant improvement in learning outcomes made public by organisations such as Pratham and Uwezo (see https://palnetwork.org). But this evidence has yet to take root in the collective mind of the education establishment in the region. For example, a study conducted by Twaweza (Lipovsek and Mkumbo, 2016) found that district officials working on education largely assess the quality of education through pass marks in national examinations and pupil progression to secondary school rather than mastery of skills.

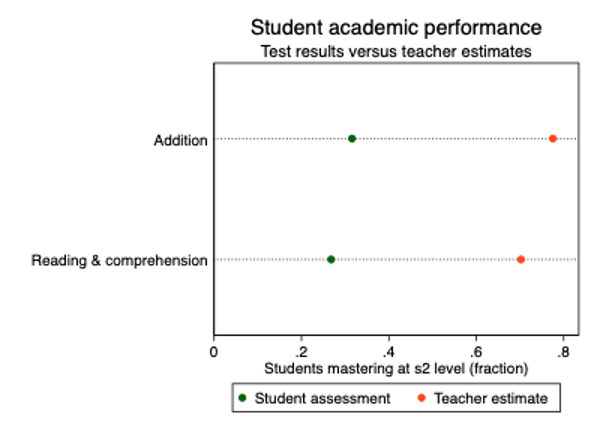

Moreover, teachers appear to have a skewed perception of their students’ capacity. In a recent nationally representative school survey in Tanzania, lower primary teachers were asked “What is the approximate share of pupils in your class that can read Kiswahili at Grade 2 level (for example a short story of five sentences); and answer comprehension questions?" An independent assessment showed that only 27 percent of their students in Grades 2 and 3 could both read a short Kiswahili paragraph and answer comprehension questions. The same question was asked for Grade 2 level addition, with similar results (see Figure). For both of these core skills, teachers estimated that about 7 out of 10 students had mastered the skill, but in fact only 3 had.

This mismatch may stem from two issues. Teachers either know the real situation but, when asked by an outsider (an enumerator conducting a survey), exaggerate their students’ performance. Or, teachers really do not have a good understanding of their students’ performance. Most likely, it is a combination of reticence, wishful thinking, and lack of tracking student results. But because foundational learning is such a fundamental outcome, conversations with teachers should not reveal such a mismatch.

Third leg: Accountability

Progress on the FLN agenda will be enhanced if national-level authorities support and accept results from serious learning assessments, rather than push back. But even if national authorities accept these findings, convincing the many thousands of teachers and parents across the education system to view the distance between measurements and targets as their day-to-day responsibility is a huge task. This brings us to accountability and organizing “follow-up” consequences to performance metrics.

The Uwezo assessments include both a data collection and a dissemination component. At the macro level, this created a platform to discuss FLN challenges, but at the household and community level, the information did not lead to personal or collective action (Lieberman et al., 2014; for a similar finding in India, see Banerjee et al., 2010).

Twaweza followed an alternative approach through a teacher performance pay program named KiuFunza (shorthand for “Kiu ya Kujifunza” or Thirst to Learn) in public primary schools in Tanzania. KiuFunza has been developed and implemented by Twaweza and subnational CSO partners, in collaboration with government and international research partners. The program targets only teachers in Grades 1-3 and is linked to independent measures of FLN: that is, Kiswahili reading and basic numeracy skills. The teacher bonuses paid average 3.5 percent of mean annual teacher salaries. There is no teacher training.

Overall, impact findings for 2013-14 and 2015-16 show that the KiuFunza performance rewards resulted in significant improvements in FLN outcomes for students in treatment schools, at current levels of teacher professional development. The most promising incentive model added three to four months of learning at less than half a month of teacher salary in bonus pay.

Based on the 2015-16 impact results, Tanzania’s Ministry for Regional Administration and Local Government asked Twaweza to formulate and test a performance pay program that can be implemented at scale. In the current implementation model, teachers are paid for every skill that a student masters, even if they do not master all the curriculum skills. At the request of our government partners, we included a school-level bonus that is linked to FLN performance and can be used to finance infrastructure improvements.

Teacher performance pay is a micro-level version of the leadership-accountability framework Girin outlines. In KiuFunza, the targets are the various curriculum skills that together represent FLN mastery, and these are clearly set out at the start of the school year. Examples are reading syllables, words, and sentences; recognizing numbers; adding up; and subtracting. The program creates tangible consequences for teachers, differentiated at the individual level, related to FLN achievement by students.

What does all this mean for the education aid architecture?

First, bilateral and multilateral donors should support FLN assessments, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. These data will be especially useful under a number of conditions: if testing methodologies and test items are comparable across countries, if many African countries participate, and if national education authorities are on board. There is an impressive amount of relevant assessment expertise in Africa, and there are large numbers of qualified testing personnel. A concrete step is for funders and donor agencies to convene relevant government officials to agree on a consistent assessment methodology and to support data collection over the long term. The data from such assessments are a necessary diagnostic instrument to support FLN progress and, subsequently, reforms to speed up FLN.

For example, the student assessment evidence provided by Twaweza and others helped to generate a number of reforms and policies. In Tanzania, the most visible reforms were Big Results Now! and its successor, Education Program for Results (EP4R). Not surprisingly, both these programs have a strong results orientation, with clearly defined goals and metrics, including learning outcomes. In EP4R, education aid disbursements are linked to progress against pre-agreed targets.

Second, test-based accountability programs in the early grades, including performance pay, deserve serious attention in education systems with weak oversight and governance. Primary school teachers in East Africa have very few one-on-one meetings with their head teacher, and they are largely left to manage themselves after their initial training. Accountability for primary schools takes the form of leaving examinations administered years after FLN should have been taught.

Teacher performance pay systems have been shown to improve student learning, particularly in low-income settings, but they are also hard for governments to implement, especially in weak education systems. A relevant question is whether public education systems can successfully outsource elements of workforce management systems to private organisations. An example of comprehensive outsourcing in Liberia is studied by Romero and co-authors (2020), where management in treatment schools was fully delegated to private providers.

Outsourcing a teacher performance pay system is a less radical management innovation, and there are a number of arguments supporting this idea. There are very few performance pay systems that operate at scale, and when they do, the implementation work (testing, payments) is typically outsourced to a dedicated technical agency or management unit. Second, performance management systems require trust in the fidelity of the metrics and promises on all sides. In our experience, a non-state actor can provide such trust. Third, many observers agree that low-performing education systems require “disruptive innovation” to improve. At the same time, there is evidence that successful at-scale reforms require the creation of new program-specific implementation capacity (Muralidharan and Singh, 2020).

A specific argument for performance pay in the context of the aid architecture is its “leverage.” As Girin notes, the scale of aid resources is small relative to national budgets. But many performance pay programs feature incentives that are small (3-5 percent) relative to the annual salaries that make up the lion’s share of most national budgets. As mentioned earlier, performance pay has the potential to generate disproportional learning effects relative to the budget.

Third, accountability and governance reform in education are only part of the FLN puzzle. Twaweza focused on FLN accountability for a few reasons: training programs did not seem very effective at the time; there was promising evidence on performance incentives; and few others were interested in actively exploring incentives in an experimental setting. However, pedagogy reform, if done well, can deliver improvements in learning that are on average larger than accountability reforms (Crouch and DeStefano, 2015). Complementarities between pedagogy reforms and teacher incentives could be a promising area for future research.

Finally, Girin remarks in his essay that there is a “yawning gap between the knowledge that has been produced and what donors and countries choose to do.” If this is true, some form of scientific accountability should become part of the aid architecture. This could take the shape of testable hypotheses at the start of a new program, with high-quality research designs to ensure that the questions can indeed be answered.

At Twaweza, we have always been interested in asking ourselves what works and what doesn't in improving learning, both through research and implementation experience. The good news for FLN is that we know how to measure it. There is also growing evidence on what works and does not work to improve FLN in weak education systems. The education aid architecture today is in a unique, evidence-rich position. The way forward is through a tight focus on FLN targets and assessments, using results from high-quality research and learning from well-implemented innovations.