Essay 16

Sleeping Soundly in the Procrustean Bed of Accounting-Based Accountability

By Lant Pritchett

Introduction

Girindre Beeharry’s essay is indeed a clarion call to action for the global education architecture. As there have been many clarion calls before, the questions now are, “Can this time be different?” and more pointedly, “What can be done differently to make this time different?”

In particular, I want to focus on both the need for, and, at the same time, the risks of strong accountability. Inducing high levels of performance from any system or organization requires structuring relationships of accountability that encourage purpose-driven actions that seek success. But, both individuals and organizations can easily adopt a key principle of many martial arts, which is to turn the strength of the attack against one’s opponent. Calls for “strong accountability” are easily morphed into “accounting” centered accountability that focuses on process compliance, and “thin” targets on inputs and outputs. In order for organizations to change, to innovate, to continuously improve at implementation-intensive tasks, I have argued (with Dan Honig) that one needs to create “account” based accountability, that empowers agents and actors with objectives and demands an account of their performance: a narrative of what they did, what happened, what they learned, and what they are going to do next.1

There is a lot to learn from bits of conventional wisdom that are not just a little wrong, but completely, totally, opposite of right, wrong. One of those is “public sector organizations don’t innovate because they are afraid of failure.” I argue the truth is that public sector organizations are built to avoid blame and are designed to be able to fail without repercussions. Being robust to avoiding negative consequences when there are outcome failures is regarded as a feature, not a bug, of public sector accountability.

I remember discussing with a World Bank colleague many years ago an early ASER report showing that in a state of India we were working with only 11 percent of children could read adequately. I suggested that introducing greater performance accountability through the democratically elected local governments could perhaps help. My colleague’s reaction was. “no, that is far too risky as local governments are weak.” To which I responded, “What is the risk here? That reading performance will fall to 10 percent?” But my colleague was, of course, wiser than I was. She realized that the “risk” that governments worried about was not the risk that children’s life chances were being spoiled and squandered by an education system brutally indifferent to them. Instead, the “risk” that governments and bureaucrats worried about was the risk of “blame.” They had an accountability system centered on process compliance, and built so that failure to educate children never led to blame falling on anyone in the system, from top to bottom.

The title of my essay comes from the Greek myth of Procrustes, who had a short bed but, at the same time, wanted his bed to fit his guests. So, his ingenious solution, now adapted by education systems around the world, was to cut his guests’ legs off so that they fit the bed. The creation of accountability systems that focus exclusively on process compliance, thin inputs (e.g., numbers of classrooms, availability of toilets, class size), and thin outputs (enrollment and grade attainment) has allowed the global education architecture and national education systems to sleep soundly on “schooling” even while “education” (learning outcomes and children acquiring the skills, capabilities and competencies they needed to succeed) was a nightmare—and, in many cases, getting worse.

Why did Education for All both Succeed and Fail?

As we in 2021 explore the scope of the learning crisis and explore ways to address it—from the global to the national to the local to the school and classroom—we want to be aware that we are hardly the first to raise and grapple with the issue of how to ensure universal quality education. We want to avoid Marx’s quip that history repeats itself, first as tragedy and then as farce.

The documents that emerged from the World Conference on Education for All held in Jomtien Thailand in March 1990 are a very sobering read in 2021. Nearly everything in my 2013 book The Rebirth of Education: Schooling Ain’t Learning and that motivate the RISE research program was already eloquently articulated in the World Declaration on Education for All, and the Framework for Action to Meet Basic Learning Needs. The preface tells us these documents were the result of an extended consultation process and emerged from a meeting of 1,500 participants from 155 governments, 20 intergovernmental bodies, and 150 nongovernmental bodies and “thus represent a worldwide consensus.”

It is worrisome that that this now ancient document has selections that sound exactly contemporary. Forgive me if I quote some at length.

Article 4. Whether or not expanded education opportunities will translate into meaningful development—for an individual or for society—depends ultimately on whether people actually learn as a result of those opportunities…. The focus of basic education must, therefore, be on actual learning acquisition and outcome, rather than exclusively upon enrolment, continued participation in organized programmes and completion of certification requirements.

Article 2, para 1: To serve the basic learning needs of all requires more than a recommitment to basic education as it now exists. What is needed is an “expanded vision” that surpasses present resource levels, institutional structures, curricula, and conventional delivery systems while building on the best in current practices. New possibilities exist today which result from the convergence of the increase in information and the unprecedented capacity to communicate.

Article 8, para 1. Supporting policies in the social, cultural, and economic sectors are required in order to realize the full provision and utilization of basic education for individual and societal improvement. The provision of basic education for all depend son the political commitment and political will backed by appropriate fiscal measures and reinforced by educational policy reforms and institutional strengthening.

Against its articulated vision “Education for All” has both succeeded and failed. The progress in expanding enrollments and grade attainments has been sustained, massive, and quite universal across countries. The calls for the “more” that was needed—more buildings, more teachers, more books—have mostly been heeded.

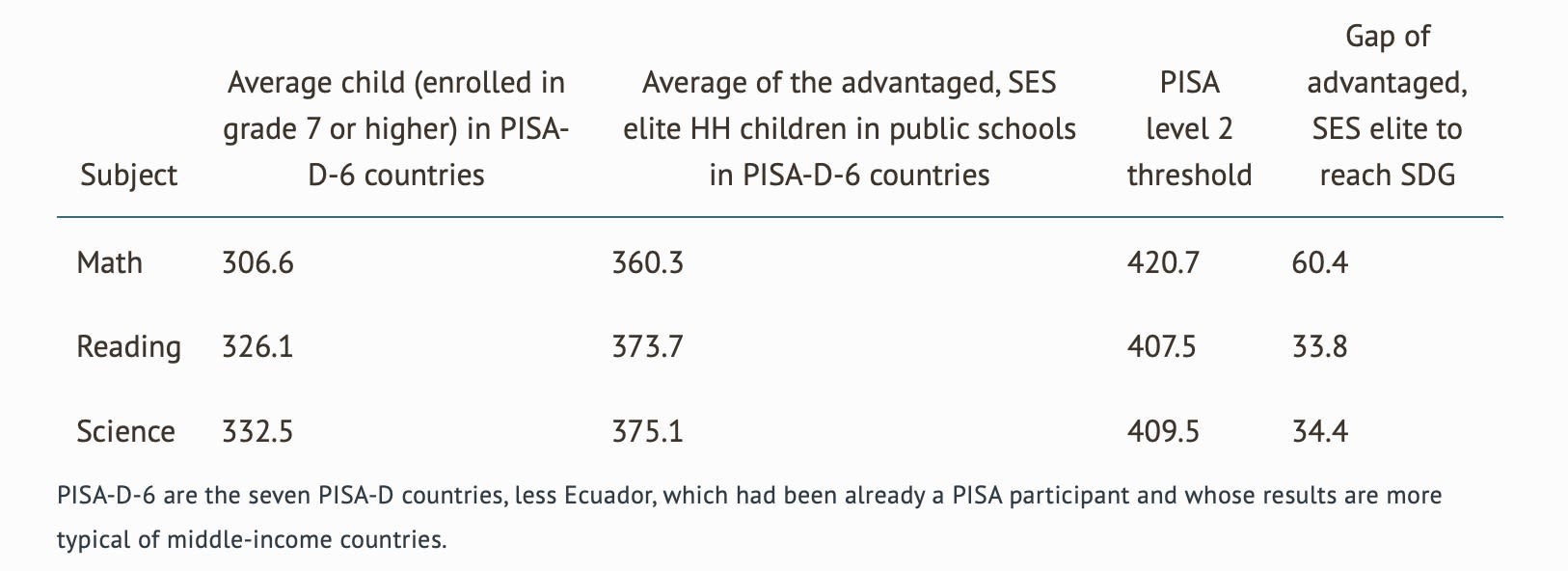

However, in many countries learning outcomes are still very, very low. Just one example comes from the PISA for Development data, from which I make two points. First, the average child, even of those who have persisted to grade 7, has very low performance. Second, while inequality in learning outcomes is large, even the socially advantaged children (male, urban, native of the country, who speak the language of assessment in the home) and who are from households in the socio-economic elite (two standard deviations above the average) are far behind (about half a typical country standard deviation) the global minimum SDG targets of PISA level 2—and almost none of them score at PISA levels 4 or above.

This is important because it indicates that it is not the case that countries have constructed an excellent education system for the elite from which others are “excluded” or “marginalized,” but rather, countries have education systems that are producing a globally inadequate education for the elite—and the disadvantaged dropouts have even worse outcomes in that system. This implies that the teaching and learning practices enacted and in which the children of elite households engage in are ineffective at producing adequate levels of learning, even for them.

Table 1. In the poorer countries participating in PISA-D even the advantaged children from SES households scored on average, fall below the SDG threshold

Source: Pritchett and Viarengo 2021 based on PISA-D data. [Pritchett, Lant and Martina G. Viarengo, 2021, “Learning Outcomes in Developing Countries: Four Hard Lessons from PISA-D.” RISE Working Paper 21/069.]

Source: Pritchett and Viarengo 2021 based on PISA-D data. [Pritchett, Lant and Martina G. Viarengo, 2021, “Learning Outcomes in Developing Countries: Four Hard Lessons from PISA-D.” RISE Working Paper 21/069.]

My conjecture is that the success and failure of Education for All (as a general proxy for efforts of the global education architecture) are sides of the same coin.

There was in fact a system of strong accounting-based accountability built into global and national systems. The data on enrollments is available and tracked in nearly every country and the UN (and other international) sources on enrollments (and its variants) are relatively complete across countries and relatively up to date. In contrast, until quite recently (with the impact of the SDGs) the data on learning outcomes at either the national or international level was sparse, lacked comparability, and not up to date. While it is not always the case that “what gets measured gets done” (as there are certainly examples of persistent measured failure), the converse is more reliable: “what does not get measured does not get done.”

The dangers of accounting-based accountability

There are several clear and present dangers from building accounting-based accountability systems too strongly around a radically incomplete measure of the desired outcomes. As is evidenced by the Jomtien documents—or any clear statement of the purposes of education—the “time served” measures of school attendance as the “output” do not capture the true outcome goals of any education system. I want to highlight three of those dangers.

First, this approach, perhaps inadvertently but nevertheless inexorably, devalues the social status, respect, and appreciation of excellent teaching and excellent teachers. That is, in any field or system where learning outcomes are actively sought after and acknowledged and respected, it is recognized that excellent teaching is a difficult and demanding vocation, and excellent teachers are recognized, praised, sought after, and valued.

In contrast, if the primary measures of the outcomes of a schooling system is time served—enrollments and grade attainment—and that is what the government and its ministers are held accountable for, then inevitably the counterpart of that as the accounting-based accountability output metric is to view teachers as custodians of warm bodies. If the school doors are open, children are enrolled in the school, and children are (mostly) in the classroom (and not making trouble or mischief outside the school), and this is regarded as “mission accomplished,” then one can begin to understand the demoralization and norm-erosion in the profession of teaching that leads to the horrific levels of both absence from schools and absence from classrooms even while in school that is repeatedly shown in data in low-performing education systems.

The emphasis on high levels of teacher absence from classrooms can easily be misinterpreted as “blaming teachers” or as a sign that there are “weak accountability” systems. But I want to emphasize that starting out with noble goals can lead, through creating strong accountability systems around limited, strictly numeric, measures of process compliance, to thin inputs, and thin outputs can lead to perverse outcomes where exactly the wrong message is being sent to “front-line” agents (teachers and principals). The message sent by only measuring schooling is that schooling is what matters, and this message devalues teachers and teaching. If all a system asks for are reports on “butts in seats” and not “minds inspired” or “competencies gained” or “human beings respected and empowered,” then one cannot identify, praise, and reward—socially through praise and honor, professionally through acknowledgement by peers, and financially—those who do those things well, day in and day out, in difficult conditions.

Second, the lack of a commitment to learning goals and an acknowledgment of the complex nature of good teaching and a strong account-based accountability system driven by learning goals also leads to IT enabled information systems (EMIS) that attempt to create a quality education through driving on “thin” inputs. My distinction of “thin” and “thick” builds from the distinction made by the anthropologist Clifford Geertz in his idea of “thick description” as a method. The counterpart of “thick” (the detailed complex rich account of our own lives we all maintain) is “thin.” As James Scott’s Seeing Like a State (details, the rise of “bureaucratic high modernism” of the civil service bureaucracies that dominate governments attempt to drive progress by reducing the lived reality of the “thick” to measurable, quantifiable, controllable “data.” 3

This conceptual approach and its organizational embodiments of “bureaucratic high modernism” are tremendously well-suited to the accomplishment of tasks which are, in their nature, logistical.4 The modern post office is a truly amazing and awe inspiring organization in its capabilities to get a letter from any one place to any other place with safety, security of contents, and reliability (see The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy by Daniel Carpenter (2001) for a fascinating historical account of the rise of the modern US Postal Service). Modern social security systems that provide income to millions of individuals promptly, reliably, accurately, and cheaply5 are, again, awe inspiring, and have had massive positive impact.

The challenge of education is that one part of providing an education—schooling—is primarily a logistical task, whereas the provision of learning is fundamentally not logistical. This means that bureaucratic high modernism as a primary mode of organizing tasks, with its top-down, process compliance, thin-input measurement approach, is well adapted to the expansion of a formal school schooling. But, as I have argued elsewhere, there is massive design mismatch between learning focused instruction that seeks to equip students/learners with skills and competencies (of whatever type) and bureaucratic high modernism.6

The danger of EMIS systems is that they create a vicious circularity in which “success” is defined exclusively as progress on the indicators in the EMIS system. This means that if the EMIS measured “thin input” is not in fact reliably causally connected to the true desired outcome then the use of EMIS has effectively blinkered and blindered governments. Pritchett and Viarengo show that if one measures learning value added of individual schools in the private and public sector, then, particularly in countries with weak state capability, the variability in performance in (measured) value added is larger across public schools than across private schools. 7 This should strike you as somewhat puzzling as it means that private schools that generally are each individually operated schools and which have no overall “top down” control to impel equality in learning outcomes produce (again, in some instances) lower variability in learning value added than do public sector systems that in large part exist to achieve equality and uniformity. Our argument is that since the “thin inputs” that the state limits itself to seeing are only very weak correlates of school performance the state creates an administrative illusion of equality and a reality of wide variance in the actual conditions for learning across public schools.

A very dangerous variant of the “thin input circularity” that an accounting-based accountability system produces is the conflation of “invest in human capital” with “spend more on a government budget heading classified as education.” I think economists have been negligent in not making the sharp differentiation between “economic cost” and “accounting cost.” Accounting cost is whatever is spent. Economic cost is conceptually the minimum that would need to be spent to achieve a given outcome. Economic cost is an optimized amount. Without a clear and agreed upon set of outcome indicators, one can easily conflate “spending more” with “getting more” when the much more likely outcome of “spending more” in a system that is not coherent around learning goals is to only spend more but not get more. Pritchett and Aiyar demonstrate that in basic education in India, the government schools’ accounting cost per student is more than twice as high as in the private sector and learning outcomes are much lower (both raw and adjusting for student quality).8 Within economic theory, if it is the case that producers are efficient at translating resources into outcomes (hence costs per output of a given quality are minimized) and one is on the efficiency frontier, then one needs to spend more to get more. But nothing could be more obvious than that most education systems are nowhere near the efficiency frontier and multiple strands of evidence show the discrepancy is very large.

Few things are more fun and rewarding for global elites, political and otherwise, than to pose as advocates for better education by issuing vacuous calls for more spending while avoiding all of the hard, nitty-gritty, and not-always-popular work of actually improving education.

Third, the lack of an accountability system built around learning goals makes effective innovation that produces progress on learning impossible. In systems that produce continuous improvements—whether in natural systems, like evolution, or in human-made systems, like economies or organizations—there are three components: generating novelty, evaluating novelty against a performance objective, and scaling novelties that are evaluated as improvements (e.g., more cost effective).

In a system with accounting-based accountability built around process compliance, thin inputs, and thin outputs, there are difficulties with all three components of innovation to improve learning outcomes: generation, evaluation, and scaling. One, without a strong and agreed upon performance measure organizations have a hard time authorizing agents to engage in innovative behaviors. Who is allowed to engage in doing something different than the standard operating practice? If one has circularly defined process compliance as the goal, then there is not space for positive deviance. Two, and related, without a strong and agreed upon performance measure there is no way of evaluating novelty. Suppose a teacher engages in some new classroom practice. Was that new practice better or not? In “time served” accountability systems, even if the new practice produces much better learning outcomes at lower cost, since there is no regular, reliable, relevant measures of the learning outcomes to be achieved, there is no functional standard for evaluating this new practice. This can produce an environment in which there is massive and ongoing generation of novelty, with lots of new and “innovative” practices being introduced each year but little or no sustained progress because the organization has no way of evaluating novelty and saying “yes” to this and “no” to that. Three, without an agree upon performance goal there is no way to effectively scale better practices, as it is difficult to induce adoption of practices, even when they are better, against the natural bureaucratic resistance to change.

This produces two phenomena that block effective innovation.

One is resistance to effective interventions that are “disruptive”9 (Christensen 1997) in that they are not “agenda conforming.” Banerji’s (2015)10 account of the introduction of “teaching at the right level” in Bihar India and Aiyar et al.’s forthcoming account of the reforms in Delhi schools are excellent narratives of how hard it is to scale effective practices in accounting-based accountability systems.

The other is pervasive “isomorphism”11 in which innovations that might have proved effective elsewhere are adopted for show or signaling or to get outside resources but without any real commitment and hence are adopted on the surface but have little or no impact. For instance, Muralidharan and Singh evaluated the adoption at scale in Madhya Pradesh India a program of “school improvement plans” that was a variant of a successful program in the UK.12 They find that the “innovation” of school improvement plan was implemented—schools did in fact produce these plans—but that literally nothing else happened. Schools did not act on their plans, supervisors did not change their supervision to assist/monitor the implementation of the plans, practices in the school did not change, hence, not surprisingly, learning did not improve. Bano (2021)13 reports on a “thick description” report on School Based Management Committees in Nigeria and finds they are having little to no impact but are continually being promoted by the national and state ministries of education but in a way that is entirely isomorphism to create among external agents supporting education the appearance of innovation, while, at the same time, allowing them to ignore the difficult issues that need to be addressed.

Conclusion

With the benefit of 30 years of hindsight, I argue that Education for All succeeded at those dimensions of education systems that could successfully be accomplished with bureaucratic high modern organizations operating with accounting-based accountability that reduced accountability to process compliance, thin inputs and thin outputs. But it failed, and in many countries failed totally, on those dimensions of education that are “thick” and require accountability systems that are coherent around producing performance on outcomes.

The strong but thin accountability for expansion in enrollments exclusively was part of the success and part of the failure. This had three downsides: it devalued teaching, it created a circularity of confusing inputs and outputs for outcomes, and it inhibited effective innovation in improving learning outcomes.

Sadly, from the narrow point of view of the bureaucratic high modern organizations (the top-down “spider” systems that dominate public schooling and the global education architecture) many of these are features of a desirable mode of accountability that allow organizations to fail on outcomes goals without blame, not a bug, even if this facilitates persistently low learning performance.

In sum, I heartily endorse the emphasis on creating strong accountability for learning performance, particularly around foundational skills, in Girin’s essay, but want to emphasize that nearly everything in the existing global and national education architecture will resist the creation of education systems with the strong performance driven, account-based accountability systems that are needed to revalue teaching as a profession, to shift away from input-driven definitions of success, and to create a system that empowers innovation.

What Girin is saying is both common sense and will require a revolution to achieve.