Essay 11

Why Haven’t We Prioritised Early Grade Literacy and Numeracy?

By Nompumelelo Mohohlwane

Nompumelelo Mohohlwane

Introduction

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 is ambitious: “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.” It encompasses a broad range of sub-goals including early childhood development through to young people entering the workforce, as well as education inputs such as teacher quality, infrastructure, and technology. While this reflects the complexity of education and correctly identifies the various building blocks, it raises the question: Amongst so many priorities, can foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN) skills be prioritised?

Girin responds that FLN has not been prioritised for reasons beyond competing priorities or overall system complexities. The reasons are, firstly, a lack of political demand for FLN; secondly, a perception that FLN skills have been mastered. In this essay, I reflect on these two reasons based on the South African experience, offering cases where the reasons hold true but also attempting to provide a deeper rationale for these decisions and the divergences and opportunities that have begun to emerge.

Tertiary education is a clear priority for all of society

The 2018 General Household Survey collected from a nationally representative 22,000 households in South Africa shows a steady decline in complaints about education. The “lack of books category” had the most complaints about both secondary and primary schools, peaking at approximately 9 percent for secondary schools in 2012 and declining to approximately 3.5 percent in 2018, with a similar pattern for primary schools, peaking at 5.5 percent in 2011 and declining to approximately 2.5 percent in 2018. During this same period, Municipal IQ, 2019reported 237 major service delivery protests across the country, mostly based on lack of services such as rubbish collection, lack of housing, water shortages, and poor local government accountability, clearly demonstrating an active citizenry not afraid of voicing dissatisfaction with government service delivery.

What is striking, though, is that none of these protests was about education outcomes in either primary or secondary schooling. While the specific statistic provided is from 2018, it reflects a long-standing absence. The only exception was the tertiary education protests #FeesMustFall between 2015 and 2016. While university students had protested previously, the 2015 to 2016 protests were national, with students expressing dissatisfaction about high fees, the exclusionary language of instruction policies in universities, and student accommodation challenges, amongst others (Mavunga, 2019). The response from the government was an increase of approximately R17 billion (US$1.2 billion) for universities over three years, directly responding to the student issues raised. This is by far the largest increase in government spending based on issues raised by students or concerning student access and outcomes.

While teachers in primary and secondary education have historically protested for higher salaries, the #FeesMustFall protests demonstrate that student outcomes and experiences can be powerful political and financial drivers. However, as argued by Girin, it is hard to imagine the same agency, political, and social pressure levers for FLN.

We do not yet have a shared understanding of exactly how poor early learning outcomes are

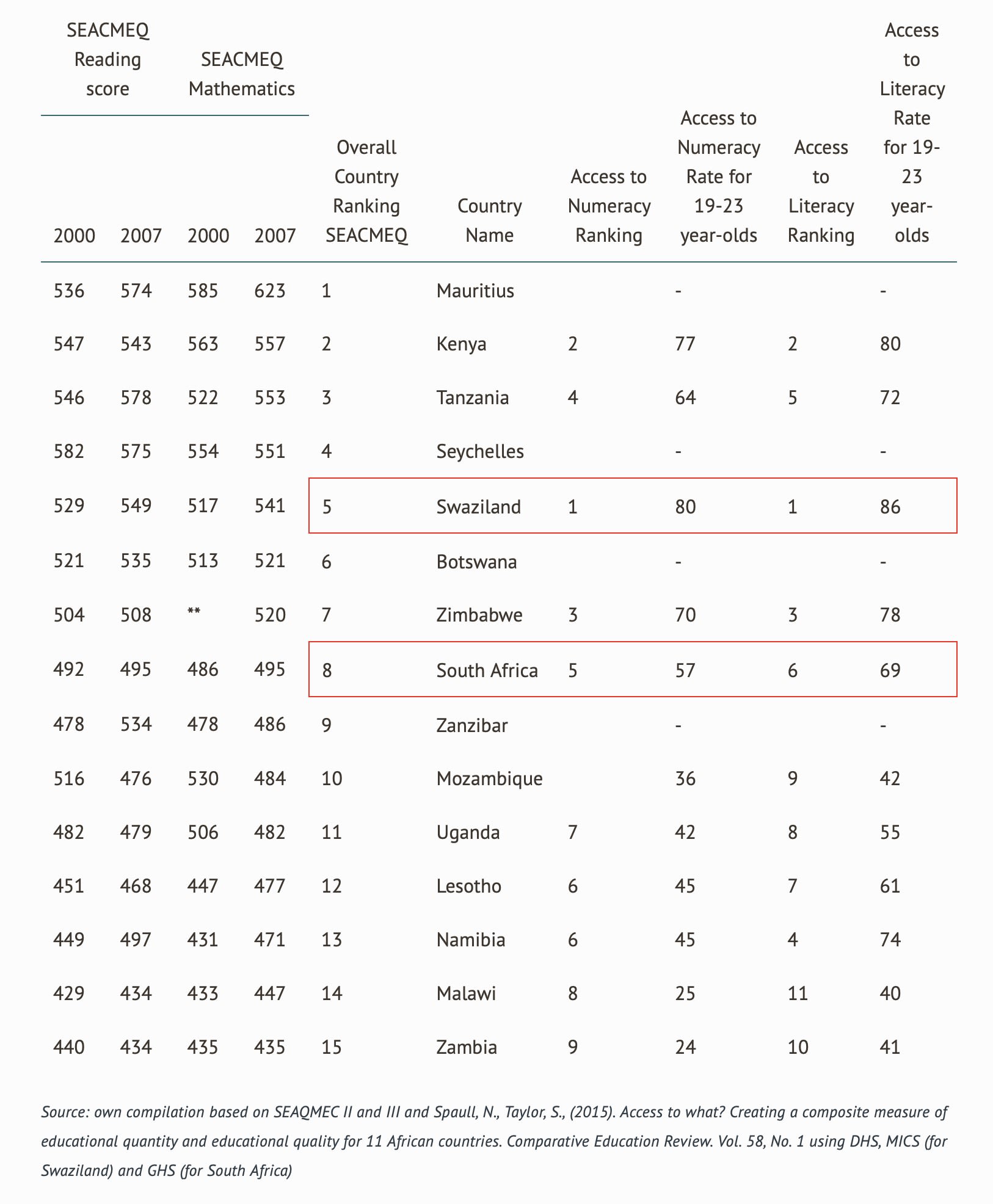

Building on the work of Pritchett (2004) and Hanushek and Woessmann (2008) Spaull and Taylor, (2015) provide a new measure that reflects both access to schooling and FLN learning outcomes. By combining learner outcomes data from the 2000 and 2007 Southern and Eastern African Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SEACMEQ) and Demographic and Health Survey data for 11 Southern and East African countries, they produce an “Access-to-Learning” measure at the grade 6 level. Their findings confirm the critique of historical international education goals that focused on access and enrolment without relating them to quality. At the same time, it highlights the limitations of looking only at outcome data, without simultaneously looking at enrolment.

If we look at Table 1, we see South Africa was ranked 8th out of 15 countries participating in SEACMEQ. However, after calculating the access-to-learning rate using the country demographic survey (or General Household Survey as it is known in South Africa) as well as a grade survival measure, South Africa is ranked 5th in access to literacy and 6th in access to numeracy. The most noteworthy case, however, is Swaziland (now renamed Eswatini), which ranked 5th in SEACMEQ and 1st in both access-to-literacy and access-to-numeracy.

Table 1. SEACMEQ score and ranking compared to Access to Literacy and Access to Numeracy score and ranking

The access-to-learning measure demonstrates the need for an earlier focus on learning as proposed in the broader FLN arguments. A key assumption in this work is that learners who have not completed grade 6—or in other words, who have not “survived the grade”—are not found because they have dropped out, which reflects poor foundational skills. This is a significant shift to typical practice where the calculation of survival rates is often done amongst education stakeholders as part of the interpretation of school leaving results at the end of secondary schooling. This work clearly demonstrates how this practice masks early learning deficits. It is already apparent that by the end of primary schooling, learning gaps are leading to learner drop-outs, and a narrow focus on only those found in secondary schools is inherently biased.

Unfortunately, this kind of analysis is not common, and system weaknesses may be underestimated especially for countries with a smaller enrolled cohort than the population numbers. Encouragingly similar work has been completed by Lilensteina (2018) recently focusing on six Francophone African countries using PASEC (Programme for the Analysis of Education Systems of CONFEMEN countries), namely, Benin, Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, and Togo. While it does not provide us with a causal link between early outcomes and adult outcomes, it provides compelling evidence that reflects on the need to consider learning levels before grade 6. Finally, participation in regional assessments such as SEACMEQ and PASEC provides a distinct level of comparability and benchmarking that is strengthened by agreement of an appropriate level of learning and competencies expected which may be more in line with international standards such as those envisaged in the SDGs.

Be careful, real change takes time

Generally, research in developing countries, including South Africa, has focused on diagnosing challenges in early grade literacy and numeracy, with less attention to interventions tested rigorously to provide substance to the call to prioritize FLN. In a book on education inequality, Taylor (2019) argues for the importance of using experimental research to identify and test effective interventions, especially in FLN. An instructive conclusion for the question at hand is that change takes time. While education stakeholders rightly desire to transform learning, change is often incremental. This is often learnt through the careful theory of change necessary when designing interventions for rigorous experiments as well as when considering effect sizes from evaluation data.

Gustafsson (2020) confirms the reality of steady progress as the informed expectation instead of rapid changes, arguing that there are “speed limits” to meaningful change in foundational skills. These are based on the best improvement rates observed from developing countries using international assessment results over time. This work was commission by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to inform SDG 4 scenarios. While the main point of my argument is that change takes more time than we would like, the magnitudes of change for developing countries are in fact higher than those for developed countries because there is more room for improvement from a low base than from those performing at the top. In addition, the kinds of changes needed to make improvements at scale in developing countries are often less complex than those needed in countries that are performing closer to a “natural” cognitive skills ceiling.

While technology and improved efficiency may accelerate this, it is prudent to temper expectations on the rate of change. Why is this especially useful? Without a well-estimated expectation by governments or international partners, the impetus to change for the sake of change rather than in a meaningful manner will persist.

What we should focus on now

While there is recognition that change at scale may occur at a more measured pace than what is envisioned by the international targets in the SDGs and other political commitments, there is a growing evidence base providing detailed interventions that have been measured rigorously to shift FLN outcomes. This includes the work of RTI in Kenya and similar work in South Africa, as summarised in the chapter by Taylor (2019) cited earlier. The dissemination of collaboratively developed guiding notes on the most successful practices, such as the World Bank guiding note on structured pedagogy and the structured pedagogy how-to- guides by RTI International, mark an important creation of a shared understanding and approach in concrete ways for FLN support at scale. The bend of international organisations, funders, and other global players should now be on supporting the implementation of these programmes and linking funding and support to this. This would be an elevation of the best collective knowledge to date.

Amidst the recognition of the move towards international convergence on the kinds of FLN support necessary for developing countries, Girin’s emphasis on monitoring and accountability for outcomes should not be lost. Most international and regional assessments (such as the Progress in Reading and Literacy Study (PIRLS), Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and SEACMEQ) take place beyond the foundation grades. While important, efforts to strengthen early monitoring and to value the outcomes as much as university outcomes is important political and societal work that is yet to be completed. Secondly, many more developing countries participate in regional assessments—15 East and Southern African countries in SEACMEQ and 13 East African countries in PASEC—than in international assessments. There are only three African countries and fewer than 10 developing countries participating in PIRLS. This is similar in the case of TIMSS, although there are slightly more African and developing countries included. It seems, then, that if we are serious about a shared measurement of literacy and numeracy in primary schooling and even for FLN, we need to use the resources, skills, and support of international organisations and partners to address barriers of access for developing countries in international assessments, as well as supporting the continued development and analysis of existing regional assessments.